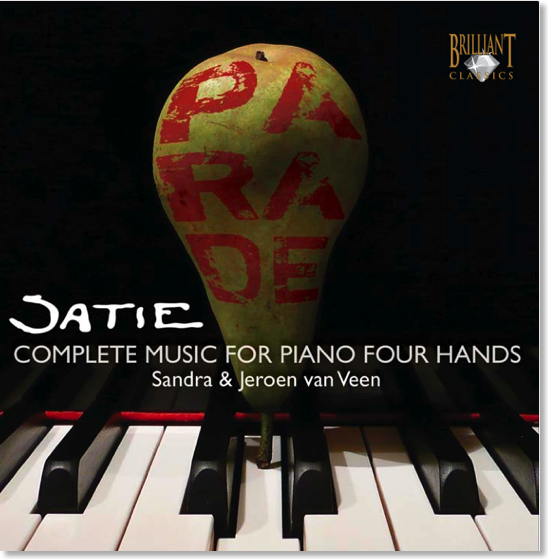

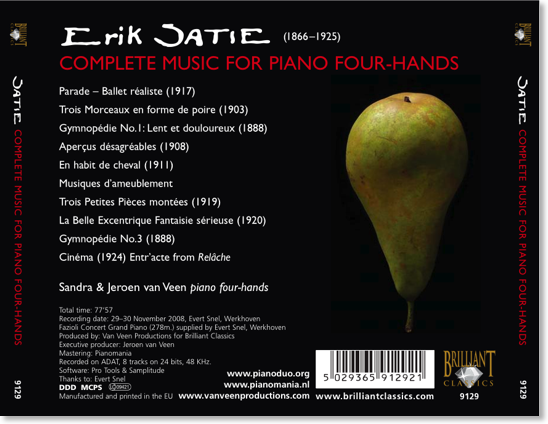

Erik Satie, complete music for piano four hands

Composer: Erik Satie

Performer: Sandra & Jeroen van Veen

Title Satie, complete music for piano four hands

total playing time: 77'57

DDD, Recorded at Evert Snel on a Fazioli 308

-Parade, Ballet réaliste (1917)

-Trois Morceaux en forme de Poire (1903) -Gymnopédie nr. 1, Lent et douloureux (1888)

-Version by Claude Debussy (1896) arranged by Jeroen van Veen (2007)

-Aperçus Désagréables (1908)

-En Habit de Cheval (1911)

-Musique d'ameublement I Tapisserie en fer forgé (1917)

-Musique d'ameublement II Carrelage phonique (1917)

-Trois Petites Pièces Montées (1919)

-La Belle Exentrique, Fantaisie serieuse (1920)

-Gymnopédie nr. 3 (1888)

Version by Claude Debussy (1896) arranged by Jeroen van Veen (2007)

-Cinéma (1924)

Entr'acte symphonique de Relâche pour piano a quatre mains, réduction par Darius Milhaud

Total playing time: 77:57

Credits:

Fazioli Concert Grand Piano (278m.) supplied by Evert Snel, Werkhoven Produced by: Van Veen Productions for Brilliant Classics Executive Producer: Jeroen van Veen Mastering: Pianomania Recorded on ADAT, 8 tracks on 24 bits, 48 KHz. Software: Pro Tools & Samplitude Recording location: Evert Snel, Werkhoven Recording date: November 29th & 30th 2008 Thanks to: Evert Snel

Piano Duo Sandra & Jeroen

Sandra Mol (1968) and Jeroen van Veen (1969) met at the conservatory in Utrecht in 1987. Since then they play together sharing their passion for multiple piano music. Their first Cd was a live recording presenting Canto Ostinato for two pianos by the Dutch "minimalist" Simeon ten Holt. This Cd was sold in more than 40 countries worldwide. Concerts and recitals brought Sandra & Jeroen from Miami to Novosibirsk. They are initiators of many concert series, among them the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and the Lek Art Festival in Culemborg. They recorded over 40 Cds in the last ten years. Besides playing piano they teach, adjudicate, compose music, and produce many different concert programs on a variety of common and uncommon concert locations such as railway stations.

www.pianoduo.org

Erik Satie (1866 - 1925)

Alfred Eric Leslie Satie was born on May 17th 1866 at Honfleur, France, of a Norman father and a Scottish mother. He began his musical studies as an organist, first with Guilmant and then at the Paris Conservatory with Lavignac. Encouraged by his harmony professor he began studying pianoforte and composition, but in 1886, after eight fruitless years and intolerant of academic rules, he decided to leave the conservatory and enlisted in the 66th Infantry regiment at Arras. A year later he deliberately caught bronchitis and was declared unfit for military service. He promptly changed his name to Erik - in honour of his mother - and published Valse-Ballet, his first work. Returning to civilian life he became a regular at Le Chat Noir cabaret, an essential night-spotfor humorists, painters, and symbolists of the era. In 1988 he composed three Gymnopédies, inspired by a poetry reading by his friend J. P. Contamine de Latour. The hypnotic allure of these compositions had its roots from in dances performed by youths during an ancient ritual celebration. The next year, seduced by the Romanian popular music and Indonesian Gamelan he had heard at the Great Exhibition in Paris, he started working on Gnossiennes. Home was a small room on the top floor of a building at Butte Montmatre: "high above my creditors". In 1891 he was engaged as second pianist at the L'Auburge du Clou, where he met Debussy who became his friend until 1916 when a misunderstanding led to a break-up that would never be reconciled. It is a well-documented fact that every day of his working life Satie left his apartment in the Parisian suburb of Arcueil to walk across the whole of Paris to either Montmartre or Montparnasse before walking back again in the evening. During this walks he frequently stopped at cafes and bars to write down ideas for new compositions. Satie was known as an eccentric and amongst other things he started his own church (with himself as only member). In these first works Satie was already using a freehand style with no bar lines, arranged chromatically around complex chord structures, that foreshadowed Debussy's harmonic and timbre experiments. In the score he would replace conventional directions such as "allegro", "piano con brio"... with his own invented terminology - "don't make your fingers blush", "from the top of your back teeth", "do your best"... In 1895 he composed Vexations, an eight-measure motif to be played forty times consecutively for a total duration of about 18 hours. A year later he took up residence on the outskirts of Paris in a modest house with huge rooms - "I have many ideas to accommodate," - where he composed Pièces froides. He accompanied the scores of these pieces with all kinds of written remarks, through which he insisted that these should not be read out during performance. In 1900 he began collaborating with the music-hall diva Paulette Darty. It was in this period that Satie immersed himself in café-concert and popular music, composing Je te Veux and La Diva de l'Empire. In 1905, tired of being considered little more than an amateur, and at odds with the musical academia, he enrolled for three years at the Schola Cantorum, where he studied counterpoint with Albert Roussel. In 1910 his music attracted the attention of Diaghilev, Picasso, Picabia, Ravel, Stravinsky and finally Cocteau with whom he became co-founder of the Les Six group. Fame, however, came with two important productions. In 1917 with Parade by Jean Cocteau and Picasso for the Russian Ballet.. However the piece that best represents Satie's spiritual legacy is Socrate (1919), a cantata for four sopranos and chamber orchestra. Satie died as he had lived, poor but surrounded by admirers, at the Saint-Joseph hospital on July 17th 1925.

Complete works for piano four-hands

The history of the piano duet is as old as that of the piano solo and almost as rich. That may be a startling idea, but let us begin to explain. The significant history of the piano duet begins with Mozart. Mozart and his sister Nannerl, popularized four-hand playing with their European tours of the 1760s. In the 19th century, piano duets were a family pastime - either four hands on one keyboard or (in homes that could afford such luxuries) two pianists at two pianos. The piano duet was the most common way people heard symphonies, concertos and other orchestral music. Most composers, up to and including Stravinsky and Rachmaninoff, published their orchestral works in piano duet arrangements, besides writing works specifically for that medium. Furthermore, there is an extensive body of piano four-hand literature, well known to piano students and music lovers, consistent of arrangement of Classical and Romantic compositions: symphonies and chamber music of Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schubert and Brahms; complete operas of Wagner and Verdi- all of them valuable sources of instruction and pleasure to the music amateur and professional of the pre-phonograph, radio, cd and mp3 days. Debussy and Stravinsky sight-read the Right of Spring once! Also Erik Satie wrote his Parade for piano four hands, to use it during rehearsals and as many other composers did in those days, to play it to colleagues and discus. Satie skipped when transcribing the Parade the Choral and the Final; I added the Choral since I always felt during performances that the piece starts somewhere in the middle. Already in 1896 Claude Debussy made arrangements by two Gymnopédies for orchestra; Debussy expressed his belief that the "Second Gymnopédie" did not lend itself to orchestration. My arrangement of this arrangement for piano was inevitable. I also added two of his five so-called Furniture Music pieces. I think they are nice to add to this Cd since I'm convinced that Satie was his time far beyond; John Cage was the first modern composer to admit his uniqueness in many regards. The first set was written in 1917, for flute, clarinet and strings, plus a trumpet for the first piece: 1) Tapisserie en fer forgé - pour l'arrivée des invités (grande réception) - À jouer dans un vestibule - : Très riche (Tapestry in forged iron - for the arrival of the guests (grand reception) - to be played in a vestibule - Movement: Very rich) 2) Carrelage phonique - Peut se jouer à un lunch ou à un contrat de mariage - Mouvement: Ordinaire (Phonic tiling - Can be played during a lunch or civil marriage - Movement: Ordinary). Both are a pleasure to play!

Sandra and I started playing the Satie four-hand music in 1990. We did one of the first internet concerts, live streaming video, with a program called Sati(r)e. We even played this theater program in our concert series in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. The music is always a great success since Satie shows many influences and styles.

In May 1917 Diaghilev’s celebrated Russian Ballet staged Parade in Paris, with music by Erik Satie and costumes and decor by Pablo Picasso. Parade was largely the creation of the Jean Cocteau, who intended the piece to represent the principles of Cubism on stage. This high concept was much enhanced by the use of striking scenic sound effects within the music score, including typewriter keys, gunshots, sirens and lottery wheels. In our recording we chose to do a pure piano recording for Parade, in concerts we add the Lottery wheel, the shotgun, the Sirens, the Typewriter (as a remark to the young soldier who died in World War I with the machineguns) and the Boat (the Titanic sunk in 1912 and apparently Satie quoted this event; the rushing 16ths at track number 5, 1:38 are representing the engulfing waves!) Parade was a special collaborator between Satie, Picasso and Ballet Russes dancer Léonide Massine: Satie was creating his first orchestral score, Picasso, his first stage designs; Massine, his first choreography. Satie's music introduced the first European rag-time and, at Cocteau's suggestion, included sounds of typewriters and factory sirens. The scandal was enormous: Debussy rejected outright Parade's antagonism, while Apollinaire was so enthusiastic he coined the term surrealism. In Zurich, the Dadaists made Satie an honorary member of their movement.

Satie wrote the score for Relâche (his second ballet) between July and October 1924, and the music for the intermission film by René Clair; Entr'acte (in which he also appeared) in November. The version on this CD, arranged for piano for four hands by Darius Milhaud, was published as Cinéma that same year. The piano arrangement for Relâche is by Satie himself. Some of this work was hurried, and in Relâche Satie incorporated repeating phrases, as well as elements of several popular tunes. Composing in this way I could easily call ‘Cubism-composing’ or ‘DaDa-music’. Satie uses music in the same manner P. Picasso and G. Braque did in their artwork.